In 1973 under the leadership of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, New York State

passed the toughest drug laws in the nation. Since their enactment these laws

have been considered the answer when it comes to solving the drug epidemic and

capturing drug kingpins. Approaching their 30th year anniversary, neither

ambition has been fulfilled. New York's gulags are bursting at their seams with

over 19,000 low-level drug offenders, and drugs are more available then ever.

Furthermore, studies have shown that treatment is much more effective than

incarceration in halting drug abuse and reducing recidivism. If the Rockefeller

Drug Laws have proven not to be effective, you might ask, why do they still

exist? In reality the harsh sentencing guidelines, with their mandatory

minimums, have fueled the prison industrial complex, in the process creating

economic development in mostly depressed rural upstate communities. Thirty-eight

prisons have been built since 1982 at a cost of over a billion dollars annually

to operate in Republican senate districts. This explains in large part why these

laws are still in effect.

I know first hand of the draconian nature the Rockefeller Drug Laws. I was a

first time non-violent offender who was sentenced to 15-years-to-life for

passing an envelope containing four and one-half ounces of cocaine to an

undercover officer in New York's Westchester County in 1984. An individual I met

in my bowling league set me up in a sting operation, when he offered me $500 to

deliver a package. My one mistake cost me 12 years of my life.

While in prison I discovered my talent as an artist and in 1988 I painted a

self-portrait titled "15 Years to Life"; in 1994 it was displayed at

the Whitney Museum of Art, which led to media exposure of my case. Two years

later, Governor George Pataki granted me clemency.

When the system released me from Sing-Sing I began speaking out against the

laws that had imprisoned me. It was then that I met Randy Credico, who directs

the William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice [http://www.kunstler.org/ ].

He wanted to know what his organization could do to fight the drug war in New

York. We came up with the idea of organizing family members of those imprisoned

under the Rockefeller Drug Laws in a manner modeled after the Argentina mothers

of the disappeared - mothers and grandmothers who regularly took to the streets,

protesting against the government's "Dirty War" torture, murder and

disappearance of accused left-wingers.

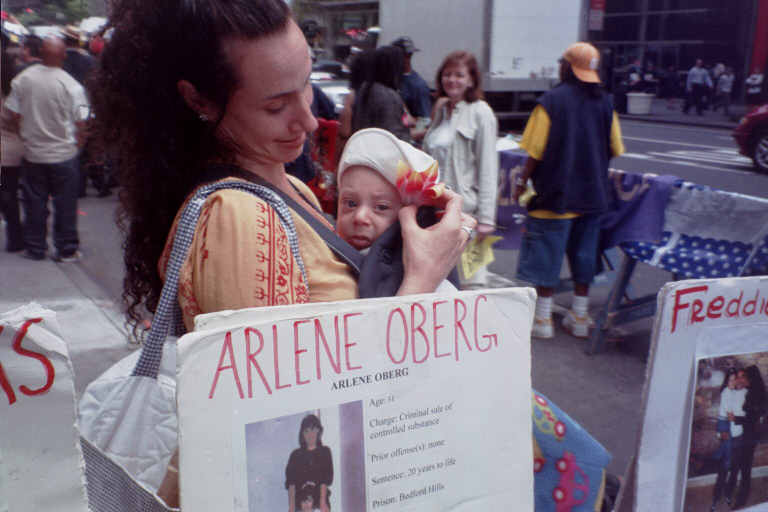

On May 8th 1998, the NY "Mothers of the Disappeared" staged their

first rally at Rockefeller Center in NYC. About two dozen family members held

signs with photos of their love ones who had disappeared because of New York's

drug laws.

This simple but dramatic gesture led to amazing media coverage. We knew at

that point we had given birth to a movement that was able to reach out to

citizens because it put a human face on the war on drugs. The event became a

weekly affair and eventually expanded to different cities in New York State.

Numerous advocates have joined our ranks. They include celebrities like comic

actor and TV host Charles Grodin, religious leaders such as Cardinal O 'Connor,

and former politicians.

With a small group of about 25 dedicated individuals, in five years we

managed to shift public opinion and changed the face of the drug war in New York

State. Once this occurred many elected officials spoke out, putting aside their

fears of political death that had been traditionally associated with drug

reform. Finally in 2001, Governor Pataki along with the Assembly and Senate,

called for reform of the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Both houses submitted bills with

their own version of what changes should be made. This triggered an on-going

battle that ended the legislative session in a deadlock.

This pushed us even more to fight for change. Since an election year for the

governor approached, we decided to use the NY Mothers of the Disappeared to

respond to the fact that many non-violent drug offenders sat in prison rotting

away while politicians wallowed in debate. An ad campaign was developed that

targeted Hispanic and black voters - a bloc Pataki seeks to placate. These

stinging ads portrayed the governor as the main reason why 94% of drug offenders

in New York's prisons were black and Latino. The governor's popularity among

this population suddenly plummeted, forcing him to seek a way to stop our

protests. For this mission the governor sent Chauncy Parker, his newly appointed

Director of Criminal Justice, to meet with us.

Parker pitched the Governor's proposed bill to change the Rockefeller Drug

Laws, detailing the formal aspects of the law. For the most part the audience of

about 20 family members listened, but did not really understand the complicated

terminology. After a while, an elderly Hispanic women who was in very poor

health interrupted him. She asked Parker how the governor's bill would help her

imprisoned son of 15 years to come home.

Chauncy stopped dead in his sentence and responded. He said if the assembly

would pass the governor's bill her son would be eligible for immediate release.

The women smiled and tears of joy ran down her face. Another black woman asked

the same question. "Immediate release" was his answer and with a

pause, he added: " If the governor's bill is passed." Everyone in the

room was full of happiness with the hope that the Rockefeller Drug Laws would be

repealed.

The meeting left us all with the idea that all the hard work we have been

doing for years had finally paid off. There was only a month left in the year's

legislative session. Hope was dwindling fast as both sides could not come to an

agreement. On June 12, 2002, the NY Mothers of the Disappeared were invited to a

meeting with Pataki. The night before, the Governor had pushed through the

Senate an additional bill that would affect only Class A-1 felons. This would

allow about two hundred prisoners to be eligible for immediate release if the

Assembly passed the bill. Not surprisingly, most of those incarcerated who would

be eligible were family members of the NY Mothers of the Disappeared.

A dilemma of moral proportions arose. Would we take the proffered carrot by

the string and support the governor freeing our love ones, even though all of

his legislation fell far short of true reform? We listened as Governor Pataki

blamed the Assembly for not cooperating with him. The meeting lasted for over an

hour. When we left, we were part of a press conference in which New York

Assembly leader Sheldon Silver blamed the governor for not cooperating with the

Assembly. We listened as our dreams of changing the Rockefeller Drug Laws began

to fade away. The 2002 legislative session ended with no resolution, leaving us

in anguish for being so close, yet so far in reforming the Rockefeller Drug

Laws.

We held another meeting on July 29th with Chauncy Parker. We found out that

serious negotiations were still being held and that the possibility of reform

existed in a special session of the legislature if they could come to some kind

of agreement. Our message to Governor Pataki, the Senate and Assembly is a

simple one. We will not take a position and support any pending legislation. All

we can say is please put aside the political rhetoric of crime and politics and

realize that there is a human element involved. Then maybe we all can walk hand

in hand on common ground to change the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

HISTORIC MEETING WITH ARGENTINA & NY

MOTHERS & NYC D.A Robert

Morganthau!!! HUGE PROTEST TO FOLLOW ON 4/15/03 IN FRONT OF GOVERNOR

PATAKI'S NYC OFFICE (READ MORE BELOW)!!!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT

Randy Credico 212 924 6980

Anthony Papa 917 754 1008

Eric Schneiderman 212 928 5578

Tuesday April 13, 10:30 Manhattan DA's office

Madres de Plaza De Mayo, Mothers of the NY Disappeared

and maverick NY Senator Eric Schneiderman to meet with New York's

foremost District Attorney Robert Morganthau

regarding Rockefeller Drug Laws;Highly Respected District Attorney is first New

York DA to

meet with families of Rock law prisoners Wednesday 4/14/ Madres and

Mothers on to Albany for

meetings with Sen. Dems, Bruno, Silver, Black and Latino Caucus

Albany Times Union 4/12/04

| Members of the Madres de Plaza De

Mayo, an Argentinean group that pressured their country's military junta

for answers about their missing loved ones, will meet with top New York

state officials Wednesday to lobby for reform of the strict Rockefeller

Drug Laws.

The madres have appointments with Senate Majority Leader Joseph

Bruno, R-Brunswick, and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, D-Manhattan, as

well as members of the Black, Puerto Rican and Hispanic Legislative

Caucus. The meetings will need a crack translator; none of the women

"speaks a lick of English," according to drug law reform activist Randy

Credico. Credico, who will accompany the madres, is spokesman for the

Mothers of the New York Disappeared, a group of formerly incarcerated

drug offenders and relatives of offenders currently serving long

sentences The New York group was inspired by the madres, who have

demonstrated every Thursday at 3:30 p.m. for years in the Plaza de Mayo

in Buenos Aires. They wear white head kerchiefs and carry signs bearing

the names and photos of the missing. The New York mothers do the same,

except their "missing" relatives are incarcerated under the drug laws,

which mandate long sentences, up to life, for sale or possession of

relatively small quantities of narcotics. "We haven't been able to

change the Rockefeller Drug Laws, yet these women were able to change a

military government in Argentina," Credico said. "We're hoping a little

of their magic rubs off." The madres, enormously popular in the Latino

community, will demonstrate in front of Pataki's Manhattan office on

Thursday, Credico said. Fellow members of the group will simultaneous

stand vigil back home at the Plaza de Mayo.

|

Argentina's MADRES DE

PLAZA DE MAYO LINEA FUNDADORA will be coming to NYC the second week of April to

join forces with the Mothers of the NY Disappeared to fight the Rockefeller Drug

Laws. A series of events are scheduled with politicians and others to

highlight the issue of human rights violations.

A delegation,

including its leader Taty Almeida, of the Argentine Las Madres de Plaza de

Mayo

www.madres-lineafundadora.org) will be making an historic 10 day trip to New

York City in April as guests of the William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial

Justice and in support of their friends, Mothers of the NY Disappeared, in their

endless and tireless efforts to change the Rockefeller Drug Laws and be reunited

with their loved ones.

Below is a partial list of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo itinerary.

Arrive April 9, JFK 6:30 AM. and will be met by the Kunstler Fund , the

Mothers of the NY Disappeared and Argentine reps and NY officials. A noon Press

conference at city hall steps with Margarita Lopez and other politicos along

with Rockefeller Drug Reform activists

Saturday April 10, A private reception with women in the civil rights

struggle at the home of Kunstler Fund founder and civil rights attorney Margaret

Ratner Kunstler; meetings with latino mothers of the disappeared in their homes

Sunday April 11: Easter in Washington Heights church TBA

Monday April 12 City Council Hearing with Mothers of the NY Disappeared

organized and sponsored by Councilwoman Margarita Lopez and the William Moses

Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice. A reception will follow inside city hall.

Tuesday April 13: MEETING WITH D.A. ROBERT MORGANTHAU!! Lunch

at offices of Drug Policy Alliance HQ at 70 west 36 street. A meeting at the

Correctional Association to hear grim testimony about Special Housing Units

Tuesday Night: A private reception at the home of longtime WMK Fund,

Mothers of the NY Disappeared supporters and fervent anti-drug war activists

Wendy and Jason Flom of Lava Records

Wednesday April 14:

WednesdayApril 14: Albany New York for meetings with Speaker Sheldon

Silver and other members of the NYS assembly; meeting with democratic leaders in

the state senate; a press conference will follow ( the mothers hope to meet with

Gov. Pataki and Joe Bruno

Thursday April 15 The Madres de Plaza de Mayo for the past 27 years have

held vigils/marches at the Plaza e Mayo in Buenos Aires at 1:30 PM EST.

OOn this day they will hold their vigil/march in front of the New York City

office of Governor Pataki on 3rd Ave and 40th streets

Thursday Night April 15 7;30PM: a party/reception/fundraiser open to the

public at Taci's on Broadway on 110 and Broadway to be sponsored by the WMK

Fund, Actor Charles Grodin, State Senator Eric Schneiderman, Documentary

producer Peter Greer, Wendy and Jason Flom and the Drug Policy Alliance

Friday April 16: TBA

Saturday TBA

Sunday April 18 return to Buenos Aires

The mothers will meet with attorney general Elliot Spitzer, mogul Russell

Simmons and longtime activist Grandpa Al Lewis during the week of the 12th.

contact:

Randi Credico 212- 924-6980

Anthony Papa 917 - 754-1008

Tony Newman Drug Policy Alliance 212 613 8026

BIO'S OF MADRES

Enriqueta Maroni,

75, has four children, of whom two were "disappeared" in 1977 by the

Argentine Junta. Their names are Juan Patricio Maroni, who was 21, and Maria

Beatriz Maroni, who was 23 when she was taken. Maria Beatrizs husband Carlos was

also disappeared. Juan Patricio studied sociology, and Maria Beatriz was a

licensed social worker. Their family was Catholic, and both Juan Patricio and

Maria Beatriz were very religious. Gradually, they became involved in a Peronist

youth movement, which was critical first of Isabel Peronâs government, and then

of the military dictatorship. They were both taken on the same night, the 5th of

April, 1977. Juan Patricio's 11-month-old daughter, Paula, was left with

Enriqueta and her husband, and they raised her. Enriqueta joined the madres de

la plaza in the fall of 1977.

.

Aurora Bellochio,

82, worked as a dress maker. She had 8 children, one of whom died in

infancy. Her fourth child, Irene , and her daughters' husband Rolando Pisoni,

were disappeared the 5th of August, 1977. Her daughter was in her third year of

studying architecture at the University of Buenos Aires, her husband was in his

fourth year of engineering at the same school. The daughter worked at the Banco

de Galicia in B.A., where she was a union representative. A year and a half

prior to her disappearance, someone went looking for her at the bank where she

worked. She managed to escape, and never went back to work and she went into

hiding, and subsequently got pregnant. She gave birth to the baby (Carlos)

in a hospital where she had been assured she would be safe by a friend who

worked there. 36 days after the birth of her only son, Irene and Rolando were

found and taken away from where they had been living in hiding. A neighbor was

given the new-born baby carlos and took him to his grandparents, Aurora and her

husband. Aurora raised Carlos as a son. After presenting her habeus corpus about

her daughters disappearance, Aurora gradually began to run into other mothers of

disappeared people, at church and at the court. Because she was working and also

had children still to raise, she did not have much time to get involved, but

eventually she joined and has become a very active Madre de Plaza de Mayo.

Carmen La Paco

, 77. Carmen's daughter Alejandra was 19 years of age and studying

anthropology at the University of Buenos Aires in the spring of 1997. Her

boyfriend was was a history student. At 11 PM on the night of March

16th, 1977, Carmen, her nephew, her daughter Alejandra and her boyfriend were

sitting around the table drinking coffee , when a knock came on the door and a

group of 9 or 10 armed thugs barged into the house. With the exception of

Carmen's mother, they were all taken to the basement of the Club Atletico, where

they were tortured for three days. At one point, Carmen encountered her own

daughter (whom she identified by her shoes, because she was chained to the

ground and could not look up). Her daughter told her that she had returned from

being tortured, and that she thought she was going to die. That was the last

time that she saw her daughter alive. Carmen says of the experience, those three

days, I lived hell. Hell not only for myself, but for what they did to my

daughter. She and her nephew, a law student, were released together after

those three days. It was a Saturday. Two days later, on Monday, Carmen did her

Habeus Corpus, and she began her fight to find out what had happened to her

daughter.

Lydia 'Taty' Almeida.

This charismatic, affable and tireless 74 year old woman actually comes from a

military family: her brother was a colonel, her father was a colonel. She has

three children. Her son Alejandro was 20 years old when he was disappeared in

1975. She says that the perception is that disappearances only happened after

the 1976 military coup, but that in fact, under the ˜constitutionalâ government

of Isabel Peron 2,000 people were disappeared, and clandestine torture

centers were established. . Alejandro, a medical student, left his house to go

out on the 7th of June, 1975, and he never returned home. Being anti-Peronista,

Taty assumed that it was the Peronist government that had taken her son, and she

rejoiced when the military coup happened. Then she realized that the

disappearances continued. When the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo formed in 1977,

Taty was hesitant about joining, because she assumed that they would think she

was a spy, because of her family âs military connections. But after awhile, she

did join, and it was "best thing she could have done." In 1985, she met

some of her son âs friends, who told her that they were alive thanks to

Alejandro, who had not told their names even when he was tortured. Since then,

she has met more of his friends, and she continues to fight. She says, Our

struggle is for memory, truth and justice.

www.stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/329/dirtywar.shtml

3/19/04

http://www.alternet.org/story.html?StoryID=18228 3/24/04

New York's Dirty War

by Anthony Papa, Mothers of the

New York Disappeared and 15yearstolife.com

On February 5, 2004, an historic march

took place at the Plaza de Mayo circle in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Traditionally

for over 25 years, Argentina mothers have come to the circle to protest against

the disappearance of their love ones from the despicable acts of the

dictatorship of Argentina, which formed in 1976. What made the day different was

that members of the Mothers of the New York Disappeared joined them. They came

to Argentina to pay homage to the Mothers who had inspired them in their

seven-year struggle against the Rockefeller Drug Laws of New York State. Two

groups of mothers from worlds apart united against the violation of human

rights.

It was a bright sunny day. The air was

sharp as crowds of tourists gathered to watch the mothers prepare themselves for

their vigil. Tens of dozens of elderly women, most in the twilight of their

lives, entered the arena of hope praying that their dedication might somehow

bring justice to the children of the disappeared. Old women from the Asociación

Madres de Plaza de Mayo (http://www.madres.org),

the most radical of several groups. began the march waving bright blue flags

proudly displaying their logo. Women with hearts full of passion whose frailed

hands held tightly onto a banner that read "Ni Un Paso A Tras!!" -- "Not One

Step Back" when translated. A sea of white handkerchiefs adorned the heads of

the Argentinean mothers as they gracefully marched in protest against atrocities

that were committed against them and their families. They were unspeakable

crimes against humanity. It is estimated that 30,000 people had been kidnapped

and murdered in the reign of terror that existed from 1976 to 1983.

In 1973, a similar reign silently

began in New York State. Men and women, many nonviolent offenders, were being

convicted of drug crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment. They had in fact

disappeared from the roles they played in society. For over thirty years, these

draconian laws have devastated and destroyed families, especially affecting the

lives of children. Although it cannot be said that the acts of the legislature

were of the same caliber as those implemented by the Argentinean dictatorship,

the enactment of the Rockefeller Drug Laws has led to the systematic

imprisonment of men and women of black and Latino decent. Over 94% of the

population of New York State prisons are persons of color. It was not a concrete

act of genocide, but no less a form of it, and for sure, a violation of human

rights.

In 1998 the Mothers of the NY

Disappeared was formed to fight to repeal these laws. In five years, using

street level protests inspired by the Argentine mothers, they managed to change

the political climate of New York State by putting a human face on the issue of

the drug war. In 2001, for the first time in 27 years, the governor of New York

along with the Senate and Assembly all agreed that the laws must be changed.

However, for three consecutive years this was not done because of disagreement

on what changes should be made. In the meantime, over 16,000 men and women

convicted under these laws are wasting away in New York State prisons.

One member of the Mothers group from

New York was Julie Colon, an aspiring actress whose mother, Melita Oliviera, a

first time nonviolent offender, had served 13 years of a 15 to life sentence for

the sale of cocaine before she was granted clemency two years ago by Governor

George Pataki. "My mother had made a mistake, and she paid dearly for it" said

Colon. "I am here to join with other mothers and family members to share the

pain of losing someone dear. Although it was not final, the act of her being

taken from my life for all those years was devastating to me." Julie was placed

in foster care. Her case is representative of many others in the New York group,

including Arlene Olberg, whose baby was born in prison while she was serving

time under the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

The day before, a meeting took place

in the office of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, the Grandmothers of the

Disappeared, a group that was formed on October 22, 1977, dedicated to finding

the children that were stolen from them. One of the vile acts of the

dictatorship was to kidnap pregnant women and put them in concentration camps

where their children were born. Then they were murdered and their children were

put up for adoption. It was a method of political repression. To date 77

children have been found through DNA testing. We spoke to their president,

Estela de Carlotto, whose own daughter was kidnapped on November 26, 1977.

Estela, an attractive, soft-spoken woman in her 70's, has felt the pain of

losing a child first hand. She said, "We had warned her of the danger, but she

wanted to change the country." Her daughter, Laura Estella de Carlotto, had been

a militant student at the university. On August 25, 1978, the military police

called her, saying that her 21-year-old daughter had been assassinated.

When asked if she was afraid to

protest their actions, she responded, "Yes, it was dangerous, some of us were

kidnapped and assassinated. But for the most part because we were women so they

left us alone. They felt we were no threat." Their perseverance paid off.

Recently the government has annulled two immunity laws protecting those who

committed the atrocities, allowing the law to be able to prosecute them. She

told us that "the new president opens his doors to us all the time because he

belongs to the same generation of the children that disappeared."

It was a similar story that was told

by a half dozen members of another group called the Madres de Plaza de Mayo

Línea Fundadora. Their office walls were adorned with photos of loved ones that

had disappeared. Some of the women had pictures of murdered family members

draped around their necks in the place of jewelry. A roundtable discussion took

place, exchanging information about each groups' struggle. At the end of the

meeting their leader suggested that she would write an open letter to the

governor of New York State, asking him repeal the laws. The letter would be

signed by many organizations that fight for human rights in Argentina. "We

thanked them for their generosity and understanding. We went there not knowing

how they would accept us," said Luciana, the wife of a former Rockefeller drug

offender who attended the meeting. "Seeing these women gives me the strength to

continue my fight to change these laws."

Some might argue that the families of

those incarcerated under the Rockefeller Drug Laws have not suffered as the

Madres in Argentina. But, I would point out that for thirty years the oppression

of these laws has been felt in the context of the social death implemented by

the punitive laws of New York State. There are haunting similarities which make

one think of what the difference is between a democratic society and a

dictatorship. For both groups of mothers, worlds apart, they are connected by

their respective struggles. One day it is hoped that both groups find peace when

justice is found.

In the second week of April 2004, the

Madres de Plaza de Mayo Línea Fundadora will visit New York as guests of the

William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice to meet with New York politicians

and others to voice their protest. Visit

http://www.15yearstolife.com/imothers.htm for more information on the

schedule of events.

Anthony Papa is cofounder of the

Mothers of the NY Disappeared. He served 12 years of a 15-to-life sentence under

the Rockefeller Drug Laws. His book "15 To Life" is being published in fall 2004

by Feral House.

MADRES FROM ARGENTINA VISIT NY AND JOINS NY MOTHERS IN ROCKEFELLER PROTEST

AT CITY HALL 4/9/04

__________________

SIMMONS RIPPED

ON DRUG LAW

New York Post

http://nypost.com/seven/12172004/gossip/pagesix.htm

December 17, 2004

www.contactmusic.com/new/xmlfeed.nsf/mndwebpages/simmons%20attacked%20over%20drug%20law

December 17, 2004

-- THE man who founded the movement to get the

Rockefeller Drug Law penalties repealed has blasted rap mogul Russell Simmons

as a "nightmare" who "destroyed" the movement.

Some of the penalties were merely reduced earlier this week — dashing the

dream of Anthony Papa, co-founder of Mothers of the New York Disappeared,

who spent over a decade in state prisons after a Rockefeller Law conviction and

launched the campaign to have the law repealed.

Simmons, who has gotten a lot of publicity for campaigning against the tough

laws, was present at a bill-signing ceremony Tuesday with Gov. Pataki,

where he called the reform "a giant step forward." The laws, passed by Gov.

Nelson Rockefeller in 1973 and 1974, meant that some low-level drug dealers went

to jail for longer sentences than rapists or murderers.

Papa, now an artist and author of the recently published "15 to Life: How I

Painted My Way to Freedom," says he was responsible for getting Simmons involved

in the movement through Andrew Cuomo.

"At first it was a dream come true," Papa told The Post's State Editor

Fredric U. Dicker in an e-mail, "but it became our worst nightmare. Simmons

the businessman's only concern was to cut a deal — he did not care a hoot about

human lives."

Papa is seething that Simmons gave up the initial goal of total repeal in

favor of "watered-down reform." He fumes, "Now people like Simmons are patting

themselves on their backs along with the governor, [Sen. Majority Leader

Joseph] Bruno and [Assembly Speaker Sheldon] Silver . .

. I should have dogged him . . . but [I] figured he would help us. Instead, he

destroyed the movement."

Simmons declined to hit back at Papa, saying that in his opinion, the reforms

were a "good deal." "In my experience as a businessman, a good deal usually

means everybody has to compromise," he says. "I'm sorry everybody's not happy.

I'm glad that something was done.

"I'm not the reason the deal got made," Simmons states. "My name is not on

the paper. But the governor did give me the pen he used, which is an honor . . .

I respect and appreciate the hard work Anthony Papa did. I'm sorry he's upset

with me."

_____________________

Pataki Signs Bill Softening Drug Laws

Published:

August 31, 2005

Gov. George E. Pataki signed a bill into law last night that

will soften the so-called Rockefeller drug laws, his office said.

The new law will allow about 540 inmates - those convicted of Class

A-2 felonies - the chance to petition for resentencing and early

release.

It is the second piece of reform to the drug laws that were passed in

1973 and that established mandatory sentences that in some cases were

longer than those for murder convictions. Last December, Governor Pataki

signed a bill allowing 446 inmates serving time for A-1 felonies to

petition for a reduction in their mandatory sentences.

The bill, one in a batch of about 100 that the governor signed about

7:30 p.m., would have gone into effect at midnight without Mr. Pataki's

signature unless he had vetoed it.

The governor, who is weighing a run for president, signed the bill

"based on its merits," a spokesman, Kevin Quinn, said.

While reformers hailed the new law last night, they said they would

like to see more done to dismantle the drug laws. "We took 2 steps

forward on Rockefeller reform last December, and we're taking another

step forward today, but we have another good 10 steps to go," said Ethan

Nadelmann, the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, a

nonprofit group focused on changing national drug policy.

___________

NY TIMES

Few State Prisoners Freed Under Eased

Drug Law

By LESLIE EATON

Published: December 15, 2005

When Gov. George E. Pataki signed a law a year ago reducing what he

called "unduly long sentences" for drug crimes, he predicted that

hundreds of nonviolent drug offenders would be released from prison.

But so far, only 142 prisoners - about 30 percent of those originally

eligible for new sentences under the revised law - have been freed,

according to a report released yesterday by the Legal Aid Society.

The new law "has not resulted in a whole heck of a lot in terms of

real impact on folks who were serving long sentences," said Gabriel

Sayegh, a policy analyst for the Drug Policy Alliance, which supports

further changes in the drug laws and organized a news conference to

publicize the Legal Aid report.

The new sentencing provisions were the most widely heralded aspect of

the Drug Law Reform Act of 2004, which changed the mandatory sentencing

laws imposed in 1973 when Nelson Rockefeller was governor.

Those laws had been criticized for requiring judges to impose a

sentence of 15 years to life on anyone convicted of selling two ounces

or possessing four ounces of narcotics, whether they were drug lords or

low-level couriers.

The new law increased the amount of drugs that trigger long

sentences, and reduced those sentences to 8 to 20 years. And it allowed

prisoners serving the longest prison terms to ask to be resentenced

under the new standards.

The Pataki administration believes the drug law reforms are working

as they were intended to, said Chauncey G. Parker, the governor's

director of criminal justice.

The goal was not to win release for all of the long-term prisoners,

known as A-1 felons, he said. "Our goal was to give 100 percent of the

A-1's the opportunity to be resentenced," and to adjust the sentences to

fit the seriousness of their crimes.

A major reason that relatively few prisoners have been released is

that district attorneys are still opposing resentencing requests and, in

some cases, asking judges to impose long prison terms, said William

Gibney, a senior attorney for Legal Aid who wrote the report.

_____________

http://www.mapinc.org/drugnews/v06/n974/a07.html?81186

The state should target the real drug kingpins

BY ANTHONY PAPA

Anthony Papa is a communications specialist for the Drug Policy

Alliance, a New York-based organization working to reform drug policies,

and author of "15 to Life."

July 26, 2006

Ashley O'Donoghue is a low-level, nonviolent offender currently serving

a 7-to-21-year sentence for the sale of 2 1/2 ounces of cocaine. In

September 2003, the Oneida County district attorney claimed that the

20-year-old was a major drug kingpin and needed to face a life sentence

under the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

Reacting to a commonly used scare tactic, O'Donoghue agreed to a plea

bargain. His A-1 felony, the highest possible felony, was reduced to a B

felony. Like magic, O'Donoghue was no longer a kingpin - that is, a drug

dealer distributing extraordinarily large quantities.

There are thousands of defendants just like O'Donoghue, whom prosecutors

claim are kingpins one day and then, through plea negotiations, kingpins

no more.

I went through the same experience in 1984 when I was arrested for the

sale of 4 ounces of cocaine. A Westchester assistant district attorney

claimed I was a major kingpin. But in the months that followed he

offered me a plea bargain of three years to life. He told me if I

refused the offer I would not see my 7-year-old daughter until she was

22 years old. This really frightened me, and I did not want to leave my

family alone.

I decided to go to trial and was convicted and sentenced to 15 years to

life. In 1997, after serving 12 years, I was freed by Gov. George Pataki

through executive clemency.

Recently, a report released by Bridget Brennan, New York City's special

narcotics prosecutor, proclaimed that kingpins and people convicted of

high-level drug offenses are being released under the new Rockefeller

Drug Law revisions. The report, titled "The Law of Unintended

Consequences," is a lopsided review of the Drug Law Reform Act of 2004.

The modest changes to the Rockefeller Drug Laws have allowed

approximately 1,000 people convicted of A-1 and A-2 drug felonies to

apply for resentencing. The controversial findings in the report bolster

Brennan's final conclusions: a clarion call for a kingpin statute and

opposition to any additional reforms to the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

Critics quickly questioned the validity of the report, claiming that it

contained skewed data and its creation was politically motivated.

The report is questionable in many aspects, but I agree with Brennan on

one point: New York needs a kingpin statute. Allowing prosecutors to

define this term has meant that people like O'Donoghue and me are

kingpins one day but not the next. New York needs a clear and reasonable

kingpin statute that can be applied to real kingpins - bona fide major

traffickers - not people convicted of low-level offenses. The kingpin

statute that Brennan calls for is both unreasonable and incompatible

with justice, because it is so broad.

Brennan's report highlighted 84 drug cases handled by her office, with

65 applicants receiving judicial relief under the new law. Contrary to

Brennan's tabloidlike insinuation that the prison gates just opened up,

each prisoner seeking resentencing had to go through a lengthy

application process in order to see a judge for resentencing.

Right now there are almost 4,000 B-level felons serving time in New York

State for low-level, nonviolent drug offenses for small amounts of

drugs. Many of the defendants have drug-addiction problems. These

thousands of offenders are not classified as kingpins. So why would

Brennan actively oppose reforms to release them? It costs taxpayers

millions of dollars to incarcerate these people when community-based

treatment costs less and has proved more effective than incarceration in

treating addiction.

Brennan needs to be reminded that the governor, State Senate and

Assembly leaders agreed reforms were necessary to equally balance the

scales of justice in applying the law with the needs of protecting our

communities.

To cause a panic by releasing a questionable report is nothing more than

additional punishment for those incarcerated and an underhanded

political tactic to stop further needed reform. If Brennan wants a

kingpin statute, let's fashion one for real kingpins, not for the

low-level offenders.

Copyright 2006 Newsday Inc.

______________

-

-

May 8 marks the 34th anniversary of New

York's Rockefeller Drug Laws. Despite a few

recent reforms, which in theory would fix

the draconian nature of these laws, little

has been done and the campaign for

meaningful reform continues. In fact, out of

the current 13,000 Rockefeller prisoners,

fewer than 300 have been freed under the

revisions to date.

In recent elections, a number of

officials who went on record in support of

real Rockefeller reform were voted into

office. Governor Elliot Spitzer, for one,

along with Lt. Governor David Paterson and

Attorney General Cuomo all have spoken out

for reform in the past. But now they are

surprisingly silent on the issue.

In 2004, I wrote a memoir of my

experiences serving a 15-to-life sentence

under these harsh laws. Andrew Cuomo, before

he became our state's attorney general,

threw a book release party for me at the

Whitney Museum of American Art. Attending

the event were prominent individuals like

Senator David Paterson, along with many

other influential guests.

Cuomo and Paterson spoke bravely about

changing these draconian laws. Spitzer, the

then-attorney general of New York, did not

attend but wrote a letter saying that my

story was a "very personal and tragic story,

like those of so many other nonviolent

offenders languishing in our prisons on

relatively minor drug offenses," and that it

"illustrates the impact that our Rockefeller

Drug Laws have had on a generation of New

Yorkers. I applaud Mr. Papa's courage in

speaking out and sharing his ordeal with the

world." It was a moving event that generated

a vision of changing the Rockefeller Drug

Laws in a positive way.

I find it strange that the people who had

supported change in the past have now become

so silent on the issue. My question is why

do politicians who use political platforms

to generate votes suddenly forget their past

when elected to higher office?

Governor Elliot Spitzer, does appear

interested in correcting the criminal

justice sector, as evidenced by his success

in removing exorbitant charges on collect

calls made by prisoners to their families,

and his recent attempt to downsize

half-empty prisons. But his laudable efforts

have not cued in on the Rockefeller reform.

Attorney General Andrew Cuomo who has used

this issue in the past to revive his

political career has not uttered a word

about it. And Lt. Governor David Paterson

who represented a highly affected Harlem

district as senator has steered away from

the issue.

Last week the New York State Assembly

passed a bill for further reform of the

Rockefeller Drug laws. Cheri O'Donoghue

joined them at a press conference and talked

about her son Ashley who is serving a 7 to

21 sentence for a first time non-violent

drug offense. This mother grieved for the

son she had lost to laws that had taken away

her relationship with him. She asked why the

Rockefeller Drug Laws had now not been a

priority with so many politicians that had

benefited from them in the past. No one

could answer her question. It's time for

Spitzer, Paterson and Cuomo to join the NYS

Assembly and step up to the plate. They

should remember their past intentions,

especially when it affects the people who

voted them into office.

_____________